The compost pile marks the sign of a knowledgeable, serious gardener. They understand it provides an invaluable source of the vital humus that builds gardener’s soil. More on humus rich soil.

Very few rules govern a compost pile’s operation. You can add almost anything organic to a compost heap.

We’ll discuss many common and some uncommon compostable materials, along with the use of certain “compost starters.”

We’ll discuss many common and some uncommon compostable materials, along with the use of certain “compost starters.”

“Natural” materials (organic and mineral), make the best soil conditioners, whether used on top of or in the ground. The action and durability of these “natural” or green materials make them far superior to the overrated synthetic chemical conditioners.

The Compost Pile A Gardener’s Tool

We call the time-honored place for all organic refuse, the compost pile or compost heap. It’s where the real gardener gets their source of humus for incorporation into the soil.

It’s important to remember that composting is a biological process, that involves bacteria, fungi and other soil organisms.

These organisms require food to do their work. Which means you need to supply the same elements your plants need for growing.

The one difference is that these organisms do not have chlorophyll and are not able to manufacture their own energy foods such as sugars and starches. They draw upon the organic matter for these foods, but in doing so use up large amounts of nitrogen, some phosphorus and potash and small amounts of other elements.

For this reason, adding fertilizers and minerals to the compost pile allows the organisms to work their best and help produce healthy soil.

- Provide temperatures to promote favorable growth conditions

- Keep the pile moist but not so wet to exclude air.

You can compost any form of organic matter that will decay. Some materials, already partially broken down such as peat moss, spent mushroom manure, spent hops and well-rotted manure. Apply these directly to the soil.

However, if a substance contains no cellulose, fiber or lignin, it will not produce humus. Dried blood, one of the most valuable of organic fertilizers, is all but worthless as a source of humus, since it contains practically no fibrous material.

Urine, a valuable source of nitrogen, urea and other fertilizer elements, is another organic substance which produces little or no humus.

Fish emulsion for plants is another non-fibrous organic material that leaves very little residue for humus formation.

This does not mean they are worthless: on the contrary these three materials are among the most valuable foods for the bacteria that work on compost. A little of any one of these will start the pile or get it working again whenever it begins to slow up.

Where To Put A Compost Pile And How To Build The Heap

Put your compost heap in light shade, on well-drained, level ground. If placed in full sun, the pile may heat up too much and kill bacteria near the surface. Considerable heat develops in the composting process itself.

Put your compost heap in light shade, on well-drained, level ground. If placed in full sun, the pile may heat up too much and kill bacteria near the surface. Considerable heat develops in the composting process itself.

In dry regions, consider making a shallow depression in the the pile to catch rainfall. But, do not make the basin so deep as to risk “drowning” the lower layer of compost.

Unless the soil in the pile area is naturally high in lime, sprinkle the area with ground limestone before applying the first layer. Sprinkle each successive added layer with limestone. The decaying processes generates acids which will slow up bacteria while favoring fungi.

If this happens the nitrogen products left behind will be ammonia nitrogen rather than the more desirable nitrate nitrogen forms. The addition of lime favors bacteria rather than fungi.

Build A Compost Pile Like A Sandwich

Build the compost pile like a giant sandwich of alternate 4-inch layers of organic matter and soil. If your soil is very heavy, consider buying extra “black dirt or composting dirt” for this purpose.

It’s not ordinarily advisable to buy outside soil, it almost always comes full of weed seed. However, composting destroys these seeds so they do not become a nuisance.

Between each layer, sprinkle a little chemical fertilizer like balanced 10-10-10 mix. Except for fish emulsion, dried blood and urine, organic fertilizers are not desirable. They too, need to rot down before becoming useful as fertilizers. They add little to the action of the pile at first.

You can add layers one at a time or build the entire pile built at once. It all depends on the available supply of organic matter dictates. After placing each layer, wet it down enough to moisten it thoroughly but not so much that it becomes soggy.

This video provides excellent information on composting and turning your compost – even during winter!

How Often Should You Turn Compost?

It doesn’t matter if all the layers are laid down at one time or over a period of weeks. Once completed turn the entire pile over and mix in one month.

The chief benefit of turning the compost pile allows the release of any excess accumulated carbon dioxide in preliminary decomposition process. It also gives bacteria additional oxygen.

If the compost looks dry after turning, wet down the pile. Turn the pile over again three or four weeks. Add more fertilizer if the pile doesn’t seem to be rotting down rapidly.

Under ideal conditions with outdoor temperatures in the 70s or above the compost should be ready to use in about three months.

When estimating if a particular “batch” is ready, don’t count any month where air temperatures average below 50° degrees Fahrenheit. Under these cool conditions the inside of the pile stays warm but the decomposition of the outer layers slow up.

You can compost any organic substance:

- Dead animals

- Bones

- Table wastes

- Grass clippings or yard trimmings

- Food scraps or food waste

- Coffee grounds for compost

- Leaves

- Weeds

- Plants pulled from flower and vegetable gardens

- Hair

- Wood shaving, wood chips and sawdust

- Spoiled grain

- Clippings from wool goods

… and many other organic wastes or substances all make good raw material for composting.

How To Get Your Compost Pile Off To A Good Start

Some recommend using special starters or “compost activators,” for “improving” the quality of the finished compost product. These sometimes include weird mixtures of herbs and other sophistications.

These “compost activator mixtures” include bacterial cultures containing strains which continue working at lower than normal temperatures. They carry some value in speeding up decomposition during cool spring or fall weather.

But, old compost pile screenings filled with good bacteria, well-rotted manure or soil from a rich field are also just as effective.

If sandy loam is the only soil available for building a compost pile, a commercial compost culture will speed breakdown. Use cultures of soil bacteria, not the herbal mixtures frequently mentioned in organic gardening publications.

No Reason For Compost Pile Smell

If properly covered with soil, no compost bin should smell or have an offensive odor. A 4-inch layer of earth absorbs all odors.

However, if blood, manures and other rich organic substances become a bit odoriferous, add a little extra superphosphate.

One caution: do not add large quantities of fresh wood ashes to a compost pile. They form lye and can injure bacteria. Mix fresh ashes with a little damp soil and allow them to stand for a day or two, after which you can use them safely.

What Organic Materials Can You Compost?

Dried Leaves – This is the most common material available to home gardeners. It’s valuable as a source of humus, but don’t take seriously the “richness” of this material.

Before trees and shrubs drop their leaves in autumn, they withdraw starches, sugars and other food elements from the leaves. Leaves are largely cellulose, so additional starches as well as nitrogen are needed to rot them.

Leaves compost best when mixed in the compost heap with such materials as stale bread, spoiled flour or meal, and so on.

Table Wastes or Kitchen Scraps – Richness of this source depends on how extravagant you are. The higher the percentage of meat scraps in table waste, the more valuable it is in compost.

Sawdust – If you have a home workshop, or if a local source of sawdust and shavings is available, wood wastes make excellent compost. If used as a source of humus, use plenty of nitrogen with these wastes. If you want compost that is less completely converted to humus, add more starchy material and less nitrogen to the pile.

Chicken Manure and Poultry Wastes – Local broiler plants often throw away offal, feathers, etc. Many poultry producers find chicken manure a nuisance and will gladly to give it away. Beware it’s high in nitrogen but not in phosphorus and potash. Add these two elements plus starch to help speed up the breakdown of chicken waste.

Brewery Wastes – Spent hops from breweries are about on a par with leaves and require about the same composting attention. One difference: hops usually arrive wet.

Seaweed and Kelp – If you live near the sea, don’t forget the sea’s free gift of kelp and seaweed. High in potash as well as many minor elements you’ll need additional nitrogen to help speedup breakdown.

Nut Shells – Pecan shells, peanut husks, coconut fiber and other nut wastes make excellent compost. One precaution: avoid walnut shells. They contain a chemical that inhibits plant growth and works like an antiseptic to kill off bacteria.

Tobacco Stems and Wastes – An excellent source of humus and a good soil conditioner when composted.

Fish Wastes – When cleaning fish, always save the offal for the compost pile. Salt-water fish in particular contribute all the minor elements as well as the three major elements in their skin, bones and offal.

Wool Clippings – Bury worn-out wool clothing in the compost pile. It will take about two years to decompose. Dark colors rot slower than light tones.

Corn Cobs – Although high in silica, corn cobs do contain considerable potash making them useful in the compost heap. Both nitrogen and phosphorus (at least a sprinkling of the latter) will improve the compost produced by corn cobs.

Sewer Sludge – If it can be had for the hauling, air-dried sewerage sludge is worth composting. However, be sure it goes through at least a full year’s decay before using. Amoeba can survive in sewerage sludge and cause infection in human beings. A full year’s composting, if the pile is turned, should eliminate them.

Lawn Clippings – Add them to the compost heap instead of allowing it to lie on the surface of the lawn, where they build up foster fungus diseases. Allow the fungi in the compost pile to work on them instead.

Straw, Hay, Cattails – Low in nitrogen you’ll need a compost “food” to rot them. The finished product closely resembles barnyard manure or yard waste.

Weeds and Discarded Garden Plants – Use these only if not visibly infected with plant diseases. If weeds have formed seed, make sure to place them deep in the pile so composting heat will kill the weed seeds.

Weeds and Discarded Garden Plants – Use these only if not visibly infected with plant diseases. If weeds have formed seed, make sure to place them deep in the pile so composting heat will kill the weed seeds.

Cotton Nolls and Wastes – Difficult to start a compost with this type of material, but it yields a high percentage of humus. Allow about a year for breakdown.

Paper Scrap – Mentioned here only because paper is often a subject of doubt. Almost pure cellulose, it requires both nitrogen and starches or sugar in order to break down. A small percentage of paper in the compost pile won’t hurt. Actually, practically anything of organic origin can be composted in time.

I read once that some some excellent compost came from a with a mixture of straw and some spoiled latex paint, combined with waste blood-albumin glue.

Can You Apply Organic Matter Directly To Soil?

Organic matter is going to give you the best soil for raised garden beds and more.

It’s the ultimate raised bed soil recipe.

Where space or time does not allow you to operate a compost pile, you can apply organic matter directly to the soil.

If done in late fall or early spring sprinkle the organic material with fertilizer and plow under. This isn’t practical during the growing season.

If not offensive in odor, use organic matter as a mulch over the soil and worked into the ground after the growing season is over.

Even though only the lower surface of an organic mulching material comes in contact with the soil, rain and sprinkling washes starches and sugars down from it to the soil organisms which consume nitrogen.

Gardeners often find their plants turning yellow following the application of a mulch. You can avoid this by adding a good mixed fertilizer on the soil before applying the mulching material.

The question is often asked:

“How much fertilizer should I apply to compost or to soil on top of compost?”

Sorry, there is not an exact formula! However, as a rough rule of thumb, add 4 ounces of actual nitrogen to each bushel of organic matter.

This dose is much heavier than you would apply to garden soil. Remember that over a million bacteria comes packed in a teaspoonful of soil and they can use far more plant food than seems possible.

Remember, you want maximum efficiency of these soil organisms in the compost pile without depriving plants of nitrogen.

Sheet Composting

Sometimes a piece of land lies idle for some time. Under these conditions, you can build soil up with sheet composting, or green manuring. Various plants commonly used for this purpose include winter rye (the cereal grain, not rye grass), vetch and buckwheat.

Sow the green manure cover crop whenever convenient, even in midsummer if irrigation is available.

Sown seed quite thickly, to produce a dense cover to keep down weeds, as well as to grow organic matter for plowing under.

The liberal use of fertilizer (to a maximum of eight pounds of actual nitrogen to 1,000 square feet) is recommended. The nitrogen will not be wasted.

Most of it will find their way built into plant tissues as protein. It will again be available to lawn grasses or garden plants when the green manure gets plowed under and rotted down.

You’ll add a surprising amount of organic matter to the soil when repeating this process for a year or two.

Winter rye works well for this purpose because if sown in fall it continues to grow every time the soil thaws in winter. After plowing winter rye under in spring, seed a crop of buckwheat or vetch to give a double supply of green matter for sheet composting.

Do not try to squeeze out too much growth the year the property is to be put into lawn or garden areas.

If planted in spring, plow the winter crop of rye under at the earliest possible date in late winter or early spring to allow for initial decomposition before sowing seed.

If seeding in August, plow under some time in July. Apply fertilizer to the cover crop before turning it under, in spring or in fall.

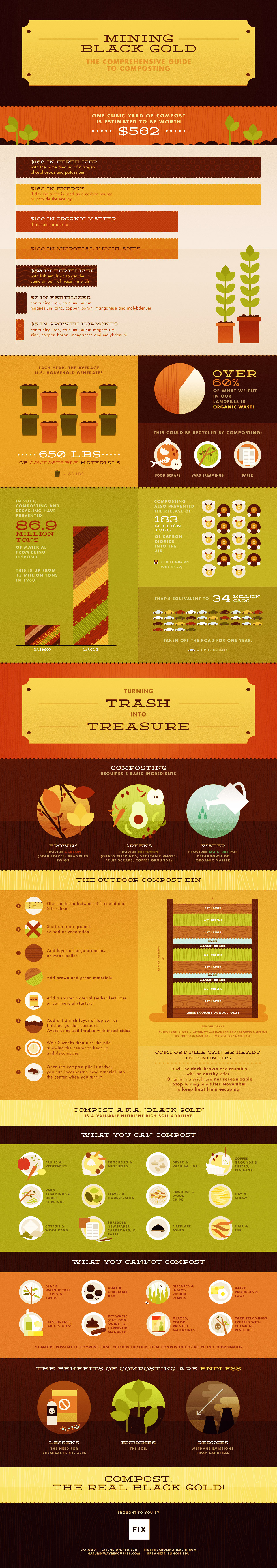

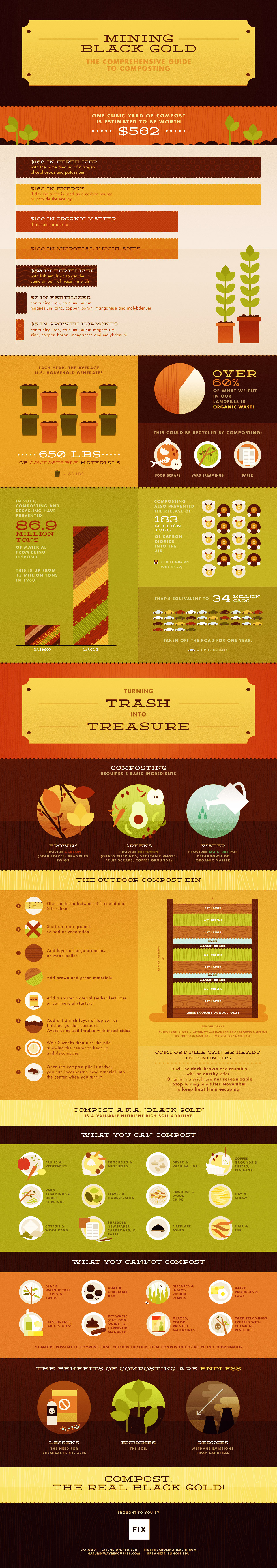

Infographic: Mining Black Gold: The Comprehensive Guide To Composting

source: Fix.com

source: Fix.com

Say Thanks to Synthetics

Don’t forget the he roles of lime, marl and ground limestone in flocculating (see video below) clay and silt soils.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=5uuQ77vAV_U%3Frel%3D0Synthetic chemical soil conditioners, introduced with such a fanfare are disappearing from the market. But they should need mentioning because of the contribution they made in calling attention to the need for soil amendment. To no small extent, awareness of this subject comes from this publicity.

Partly because of their high cost, the products introduced are not likely to come back. But with the idea once started, who knows what combination of science and commercial enterprise may find a way to make new forms of such materials practical and economical?

Physical Conditioners

Adding minerals which increase porosity by mechanically opening soils to air and water is another method of improving soils.

One of the oldest materials used for this purpose is ordinary sand. The addition of enough sand to a stiff clay soil should, in theory, separate the particles so air and moisture content can move in freely. This should “correct” the soil so it will crumble readily when squeezed into a ball.

Sand should provide pore spaces in which bacteria and fungi can thrive. This in turn would gradually improve the humus content so that a clay soil would turn into a clay loam.

Unfortunately, adding sand doesn’t always improve the clay soil. Often it requires large amounts to bring about any worthwhile improvement.

In the final mixture of the two there should be at least one third sand and not more than two thirds clay.

When not adding enough sand and separating the clay particles, it acts like the aggregate in a concrete mixture. The individual grains become cemented together by the much finer clay particles to form an almost impervious solid.

For example, 20% sand was once added to stiff clay. The mixture became so hard it resembled a cement sidewalk. But when another inch layer of sand was spread on top of the soil and worked in with a rotary tiller, the whole mass crumbled and fell apart like magic.

For this reason, when using sand to modify clay, say to a depth of 6 inches, spread at least a 3-inch layer of sand over the entire area. This makes sand a somewhat expensive soil conditioner if a sizable area needs treatment.

Porous Minerals

Two “expanded” minerals – vermiculite and Perlite – have one thing in common – a porous structure which enables them to absorb enormous amounts of water.

They make excellent soil conditioners and, unlike either organic matter or chemical conditioners, they remain practically unchanged for years.

They are chemically inert and not readily attacked by soil acids or alkaline solutions. While more expensive than most other materials, they come with very definite advantages.

Clean, easy to handle, readily available and, for all practical purposes, sterile when they come out of the bag. They are convenient to use for seed starting or cutting propagation, for house potting soils and for small garden areas.

If the material is to be “seen” at the soil surface vermiculite it looks more like soil. The white color of Perlite produces a less natural soil mixture in appearance.

Both Perlite and vermiculite can be used in amounts up to one third the total volume of the soil. However, they need not be used as freely as sand. Relatively smaller amounts of either material will bring about noticeable improvement in a soil.

h/t – R. Milton Carleton

source: Fix.com

source: Fix.com